Risk Controls in Electronic Futures Markets: How Exchanges Balance Volatility and Stability

- Michael Biagioni

- Jun 30, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jul 21, 2025

By ExchangeHub – Former Manager of Market Operations, CME Group

In today’s electronic futures markets, volatility is part of the job. The challenge isn’t eliminating volatility; It’s knowing when and how to pause the market just enough to keep it functional without disrupting legitimate price discovery.

As someone who managed market operations at one of the world’s largest exchanges, I’ve seen firsthand how complex and interdependent these systems are. At ExchangeHub, we help demystify how risk controls work so traders, brokers, and infrastructure teams can better navigate fast markets.

This article walks through the core price risk controls implemented at CME Group and explains how they work together to balance risk and resilience.

No Silver Bullet: Why One Control Isn’t Enough

One key message from years of real-time experience is that no single control can catch everything through countless market events, from routine roll periods to exceptional volatility like we saw during COVID or the more recent Trump tweets. The lesson was clear: markets need multiple risk controls working together.

That means using overlapping protections across different time frames and price movements. The aim is to catch fat finger errors, runaway algos, and flash crashes while letting real volatility play out. Volatile doesn’t mean bad. That’s why market participants use futures markets to manage risk.

Price Banding: First Line of Defence

The first and most basic control is price banding, which helps prevent erroneous orders from executing outside a sensible range. This acts as a fat finger protection.

For example, if WTI crude oil (CL) trades at $65, a trader can bid $60, $64.50, or even $65; there’s no restriction on placing lower bids. But if someone tries to buy above or sell below the current price, plus or minus the band value (in this case $0.50), that’s when price bands kick in. If an order is outside the allowed band, it’s rejected before it reaches the matching engine. The trader also gets a rejection message showing the start price and the violated upper or lower band.

The diagram below provides a visual representation of how Price Banding is applied.

Bands are dynamically calculated for each product based on a reference price (e.g., last trade, bid/ask midpoint). For illiquid or deferred contracts, a theoretical price estimates a reliable reference price so that valid orders aren’t wrongly rejected.

Why is this so important? A bad trade at the wrong price doesn’t just affect one market; it can ripple through related spreads, implied orders, or sophisticated algos trading synthetic inter-market spreads across different exchanges.

Velocity Logic: Too Far, Too Fast

Where price banding handles single-price errors, velocity logic is there to stop markets from moving too far, too fast–even if trades stay within the allowed bands.

There are two types used at CME:

Velocity Logic Wide (VLw): Typically 3x the banding value, this triggers if the price moves in any rolling 1-second window.

Velocity Logic Narrow (VLn): Typically equal to the band value, this uses a 1-millisecond window, specifically configured to catch cascading stops or aggressive low-latency algos.

Why both? An algo could artificially walk the bands up in incremental steps that fall within the band values, potentially circumventing price bands, leading to runaway prices. Price banding wouldn’t stop it, but velocity logic would.

When triggered, the market enters a Pre-Open state for 5 seconds. During this pause, the order book can become crossed as orders may be submitted or cancelled.

The engine then calculates and publishes an Indicative Opening Price (IOP) based on matching the most volume from available bids and offers.

Once established, the book uncrosses and trading resumes. This happens frequently in fast markets, and the system allows for unlimited velocity logic triggers in a day.

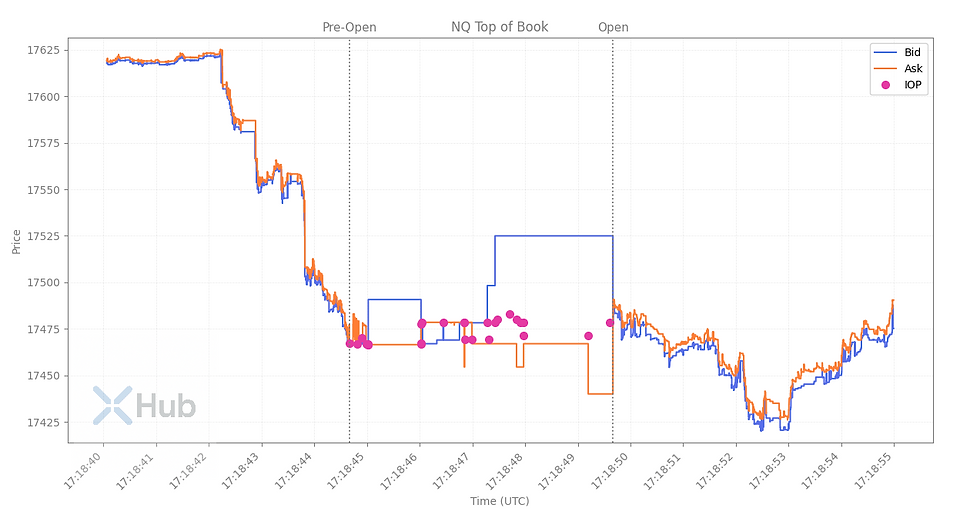

The charts below illustrate a Velocity Logic event in practice.

On April 9, 2025, a tariff pause announcement triggered sharp volatility, resulting in multiple Velocity Logic events in Equity Index futures.

The first chart shows the temporary trading halt as the market enters a Pre-Open state.

The second chart displays the crossed bid-ask spread and IOP during this period.

Dynamic Circuit Breakers & Limits: Slowing Down the Big Moves

Beyond price banding and velocity logic, CME implements dynamic circuit breakers (DCBs) for larger, longer moves. These work the same as velocity logic but with a 1-hour rolling window, a longer pause, and a dynamically defined percentage threshold calculated from the previous day’s settlement.

For example, if crude oil settled at $60 the previous day and has a 10% DCB, a $6 move in any direction would trigger a 2-minute pre-open.

That pause gives traders time to reassess the market, enter new orders, or cancel resting ones. The engine calculates the indicative open price, and after two minutes, the market reopens.

DCBs are applied to energies, metals, FX, interest rates, and major overnight equity futures.

Daily Price Limits

These are hard limits used primarily in U.S. agricultural products (and overnight equity index sessions).

Once the limit is reached, the market remains open, but no trades can occur outside the limit range.

Unlike DCBs (which are dynamic and intraday), these are fixed for the session and don’t trigger a state change or pre-open.

Market-Wide Circuit Breakers

These are coordinated halts across U.S. equity markets, triggered by broad index declines.

Trigger levels: 7%, 13%, and 20% down moves from the previous close

7% / 13%: Futures enter a 10-minute pre-open; U.S. equities pause for 15 minutes

20%: Markets close for the day

This applies to major U.S. equity index futures (e.g., E-mini S&P, Nasdaq) and is linked to the cash equity markets.

Error Trades: The Last Line of Defence

Even with all these controls, trades can still get through that shouldn't. That’s where the Error Trade Policy comes in.

If participants believe a trade was erroneous, they can call the Global Command Centre (GCC) within 8 minutes to invoke the Error trade policy. The trade is reviewed using a Non-Reviewable Range (NRR), a predefined buffer around the fair value. If the trade falls outside the NRR, the price may be adjusted (not busted, unless under exceptional circumstances).

Monitoring and Adjustments

From my time at CME, we reviewed all thresholds quarterly. We made adjustments based on price banding reject frequency, and changes in a product’s volatility or liquidity relative to its current risk parameters.

Any adjustments were made system-wide, since the controls are interlinked. For instance, widening a price band would require adjusting the NRR and velocity logic thresholds.

Control events were also monitored in real time. Our teams tracked rejections, VL triggers, and system behaviour. Additionally, the regulatory department reviewed each velocity logic and DCB event after the fact.

Final Thoughts

From my experience, the best risk controls are those that support trading, not interfere with it. They allow genuine volatility while catching anomalies early enough to prevent wider damage. Risk controls aren’t about predicting what will happen but about creating space for participants to make better decisions when things move quickly.

Contact ExchangeHub for a complete walkthrough of how these controls operate across different exchanges.

Comments